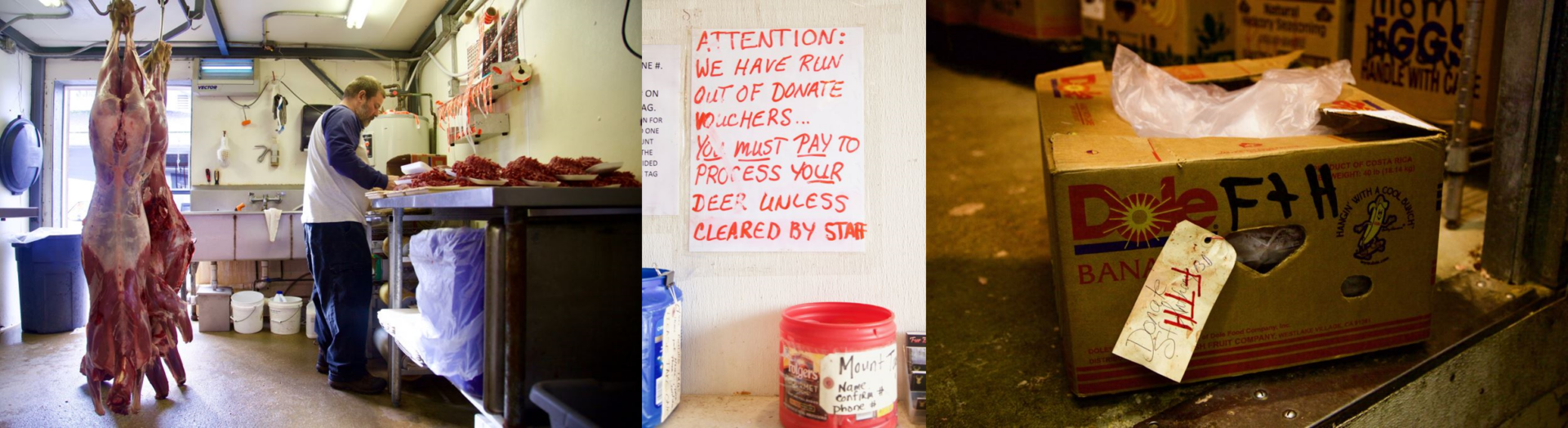

STAFF PHOTO BY DANDAN ZOU Mike McWilliams looks at a donated deer for the Farmers and Hunters Feeding the Hungry program.

STAFF PHOTO BY DANDAN ZOU Mike McWilliams looks at a donated deer for the Farmers and Hunters Feeding the Hungry program.

Meeting the Need for Meat

By DANDAN ZOU dzou@somdnews.com

The idea of sharing a bounty of a harvest with others may not be a new concept, but a nationwide program named Farmers and Hunters Feeding the Hungry has made it their mission to connect local hunters and food banks to make meat donation easier and speedier.

The organization pays certain butcher shops in local areas processing fees ahead of time and connects verified food pantries with the shops so boxes of frozen meat can be delivered directly from shops to the pantries.

In the eyes of many, this approach is a win-win for both those who hunt and those in need.

‘Farming the deer to feed the people’

Hunters love getting down to the woods and they love hunting, said Mike McWilliams, who runs Wild Game Processor in California. “But they don’t want to take deer for no reason.”

Born and raised in Leonardtown, McWilliams said he worked on a farm when growing up and saw the damage deer can do to farmers’ crops. His shop has been a FHFH participant since the program first started in 1997 because he believes the program helps hunters, farmers and those in need all at once.

He added that deer meat could be a “renewable resource” for years to come if managed well.

“The state regulates how many deer you can take, keep the population in check,” McWilliams said. So the deer can continue to multiply and the supply will never dry out.

“It’s like farming the deer to feed the people,” he said.

McWilliams’ processor shop and Mike Ridgell’s Whitetail Butcher Shop in Dameron are the only shops in St. Mary’s that participate in the FHFH

program.

A member of the Ridge Volunteer Fire Department, Ridgell runs the butcher shop part time, mostly on weekends. He joined the program a few years ago for the same reason McWilliams did. He likes the program and what it offers.

“A lot of people don’t realize there’s a lot of poverty in some areas in this county,” Ridgell said.

According to the numbers provided by FHFH, Southern Maryland donated close to 270 deer and livestock last season, which equates to more than 10,000 pounds of meat and 42,000 servings.

McWilliams’ shop usually processes between 80 to 100 deer a year, he said. The cost of processing one deer is usually $70, but McWilliams said he does it for the FHFH program at a reduced rate.

After the discount, it costs the program less than $1 for each pound of venison, according to McWilliams.

“You can’t get any kind of meat for under $1 these days,” he said, adding especially not the type of “high-quality, high-protein, lean deer meat” that he processes.

The deer donation also fills in a critical gap among many food pantries that often don’t have enough raw meat to serve. Due to preservation concerns, few meat donation comes from community food drives.

The First Saints Community Church’s soup kitchen, for example, receives about half of its meat donation from the FHFH program, according to Carol Barton, the church’s soup kitchen coordinator. The other half comes from the Southern Maryland Food Bank in Waldorf, for which the soup kitchen pays 50 cents a pound.

Barton uses some of the venison in cooked meals for the soup kitchen. The rest goes in pantry bags that the church gives away to people who come in to take home.

“It comes in very handy for us,” Barton said. “Without it, there are times we don’t have meat to serve at the soup kitchen or for folks to take home.”

From local to local

Kel Christianson of Owings said he heard of the program from another hunter friend who told him if he happens to have more deer meat than his freezer could hold, he has another option that could help other people out.

Most hunters learn of the program through word of mouth, Christianson said. He has not donated any deer yet, but he said he plans to soon because he likes the idea that the food will go to benefit people locally.

And that was the intention of FHFH. The organization’s primary roles are raising funds to pay for the cost of meat processing and verifying local partners, both butcher shops and food pantries, according to Josh Wilson, executive director of FHFH.

“From there, we hand it off to local agencies already in place,” Wilson said.

This approach allows FHFH not to duplicate efforts in distribution and at the same time keep the meat local, which is an appealing aspect of the program for hunters who can be sure that their donations will help those around them, Wilson said.

The idea of setting up such a program occurred to Wilson’s father, Rick Wilson, when he helped a woman on the side of the road picking up a road kill deer that she said she would rely on to feed her family.

The concept of using wild games to feed the hungry, Rick Wilson later found out, was nothing new. He learned that similar programs had already existed in Virginia and some other states. Through his church in Hagerstown, he used the same approach and founded an early version of what is now known as the FHFH program. Once a small service group, FHFH has grown to become a nationwide nonprofit organization with about 120 volunteers in 30 states in just a few years.

Funding is a challenge

Since July, McWilliams has processed about 70 deer, averaging about 50 pounds a deer. The number is a little behind compared to previous years. But he believes the pace will pick up as cold weather settles in, which will result in more deer movement. What’s concerning at this point of the season to him is not the volume of the donation, but the cost of processing those donations.

This year FHFH decreased his quota from a record high of 120 about a couple of years ago to 35 this year.

“I’m not gonna turn any deer meat away,” McWilliams said, knowing he might have to shoulder that cost himself later.

By the end of the season, McWilliams hopes FHFH would have more funding coming in and therefore give him some reimbursement.

That is something FHFH is not sure of themselves at this point. In general, Wilson said FHFH does not encourage the butchers take in more donations than what they are assigned to at the beginning of the season. FHFH usually mails the allocation vouchers to local shops in August so butchers know their quota for the season, which generally runs from July to the following June.

If local processors are approaching the number they are given, Wilson said FHFH encourages them to contact the program to see if more funding is coming in later in the season, and if they could work something out.

Darrin Weimert, who runs Rowell’s Butcher Shop in Prince Frederick, is taking FHFH’s advice. He had posted a notice upon entrance that his shop has “run out of donate vouchers” and hunters must pay themselves to process the donated deer. The processing fee is $80, and he charges $70 per deer for FHFH.

“This is the first time I had to turn away a donation,” Weimert said. His shop, FHFH’s only participant in Calvert, has been processing meat for the program since it was established in the state. The number of deer processed dropped from a record high of 150 a few years ago to about 80 this season, as of early December.

Funding was a key resource that fueled FHFH’s success over the years. But butcher shops and soup kitchens across Southern Maryland are feeling the impact of the program’s funding decline.

Two weeks before Christmas, Barton’s soup kitchen ran out of meat and she said she used canned tuna, canned chicken and peanut butter in

replacement to provide some form of protein in a meal.

The FHFH program largely relies on state funding and local grants, Wilson said. The nonprofit group has a list of supporters and organizes a few fundraising events throughout the year.

During a record-high season between 2012 and 2013, the organization received $248,000 through the Maryland Department of Natural Resources, Wilson said. But that number dropped to $50,000 this season, which represents about one third of its total budget in Maryland.

“We are not complaining,” Wilson said. But “this reminded us that you can’t rely on large funding, but you need to build your own sources, go back to the roots of the organization and rely on efforts of the volunteers.”

In mid-December, McWilliams contacted FHFH, and he said the program raised his quota from 35 to 50.

As the season goes on and the donations keep coming, McWilliams is thinking about partnering up with some local churches to fundraise for this cause so he could keep processing the donated meat.

But that is still in the preliminary stage, “in the works,” he said.

Farmers and Hunters welcomes new supporters and volunteers to join our cause. To make a secure online donation, CLICK HERE. Any amount you can give is appreciated and will help us continue to provide needed meet to the hungry. CLICK HERE to learn more about volunteering with FHFH.

staff@fhfh.org

staff@fhfh.org  301-739-3000

301-739-3000